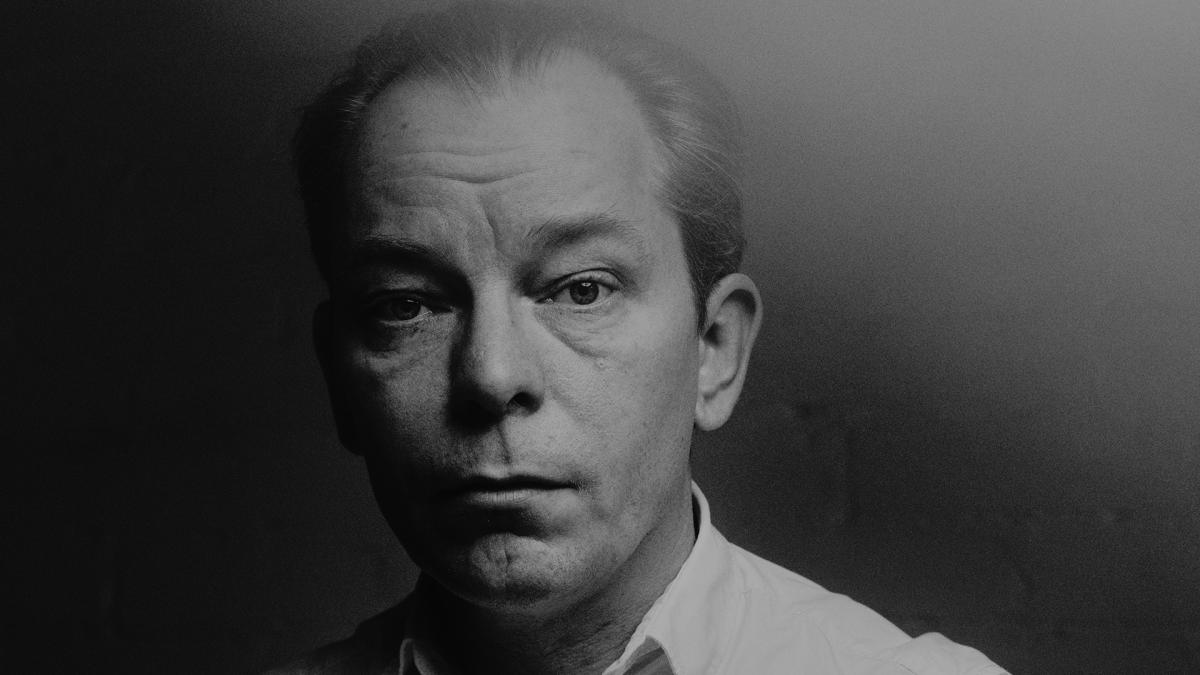

Tero Nauha: Fostering the autonomy of universities’ education and research is challenging under pressure from the market economy

The funding system for arts education needs a makeover, which requires the building of a bridge between the arts sector and critical financial thinking, says professor of Live Art and Performance Studies Tero Nauha.

“Applying operational models derived from the business world in the context of arts education is a major cause of headache,” says professor of Live Art and Performance Studies Tero Nauha.

The Finnish universities do not charge tuition fees for students coming from Finland or other EU/EEA countries. This is possible because they receive a core funding allocated by Finland’s Parliament. However, the core funding is limited, and universities are directed to acquire external funding, as well.

Currently, the models that are being applied to arts education in Finland have established indicators for artistic activities. Some of these indicators that determine how much government funding the university receives include the number of published articles and the number of completed degrees.

“Models that measure productivity are a bad fit for pedagogy in the arts, because the intrinsic value of art isn’t monetary.”

Too big a risk

The universities are constantly struggling with the conflict of fostering the idea of an education- and research-centred university that is not focused on financial gains while keeping up with the requirements of the market economy. From the very start of their studies, arts students are regularly encouraged to pursue careers as entrepreneurs and driven to fill in grant applications.

Artistic works that require risk-taking may never see the light of day if measuring their value in money is so laborious that the risk of investing in them is considered too big. Nauha finds that the message that society is currently sending contradicts with the notion that artists’ work is significant in and of itself.

“In practice, it’s impossible to take risks if the grant application includes a section where the artist has to describe what their project yields. The arts sector should forge connections to critical financial thinking. This way, funding for arts education could be reformed through a system where funding would support students’ lives instead of making their lives challenging and fragmented, as is the case at the moment.”

Financialisation narratives’ impact on the arts institutions

So how could this bridge be built?

A project led by Nauha, “Financialization of Arts education, Practice and Research”, may provide some answers to this question. The project explores narratives that are connected to global financialisation and that have an impact on the social reality and the cultural knowledge economy within institutions.

Uniarts Helsinki will host this year’s ELIA arts education conference, where representatives from European higher education institutions in the arts gather biennially to share their views on topical themes in the arts sector.As part of the conference, Nauha will give a presentation where he inquires into some of the effects that financialisation has had on higher education in the arts and research in the field.

Financialisation means the increasing power and relevance that the financial markets have in society. The mechanisms, models and narratives of financial markets have spread over to other areas besides economy, including social relations and decision-making. People have begun to view education from the perspective of investing.

More autonomy in art making

The concept of financialisation originates from critical finance. The usage of the term began in the early 2000s when students turned into investments, for instance through Social Investment Bonds, where productive performance, the labour, could be measured as ‘social’ investment.

What this means for Nauha’s work as a professor is that he must apply for external funding, write articles and promise that students in the programme graduate within the normative duration for studies.

“I do see the meaning in applying for external funding, but usually it’s in no one’s best interest to have a student graduate in a terrible rush.”

In the 1970s and 1980s, for example, there was more room to experiment and to take even bold risks as an arts student. Without these elements, the field of arts will become narrower. Then again, funding in the recession-torn Finland of the 1970s was scarce and limited all around.

“There was more autonomy involved in art making. There was no need to constantly think about how I could sell one of my qualities to someone,” Nauha says.

Critical narratives

What fascinates Nauha the most are the things that economy and art have in common. Both fields build up narratives and look forward to the future in the light of these stories. Not all narratives should be maintained, however, and there are certain economic narratives, sold by the market economy as the only real truth, that should be dismantled, as has been stated by economists such as Mariana Mazzucato. These are the narratives that Nauha, too, is interested in exploring.

Economy should not be considered purely evil in art-related discussions. Nevertheless, economy, ownership and money can be examined from various, even critical points of view. There is a need to build bridges between art and critical economic reasoning so that there would be a fruitful dialogue between the two.

“We should make critical thinking in the economic sector intersect with critical thinking in the arts sector. It’s possible to dismantle economic concepts, but it’s not very easy, and it can’t be done alone.”

This is the bridge that Nauha’s research project aims to help build.

Text: Susanna Bono