Professor André de Quadros: In an increasingly polarized world bringing people together is the first priority

“Music education has enormous potential to foster changes of attitudes, to generate a sense of self, to heighten awareness, to lead people towards activism. Music-making is a vital way to address the social issues of our time.”

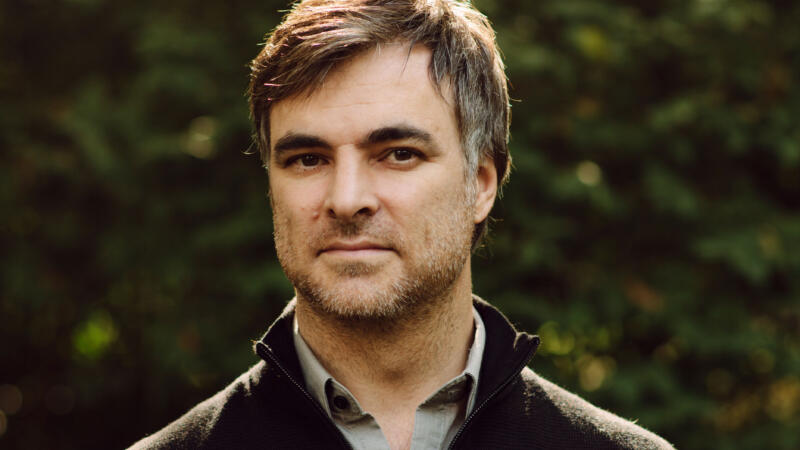

André de Quadros is professor of music at Boston University with affiliations in African, African American, Asian, Jewish, Muslim studies, prison education, Forced Migration and Antiracist Research. He has been working with very diverse audiences as a music educator, composer, musician and also as human rights activist.

Your work spans a remarkable array of disciplines and settings from music, education to human rights activism. What inspired you to blend these diverse fields together and how do they inform and enrich each other in your practice?

My work in music education and activism are interwoven. When I was in college in India in the 1970s, I fell in love with Western classical music, particularly with conducting. At about the same time I was passionate about decolonization and the issues of colonial domination. These two love affairs were in collision, of course. After all, classical music in India is a continuing colonial legacy that the anti-colonial discourse challenged and resisted. But I pursued them both as separate passions.

As a director of choirs and choral projects in various parts of the world, how do you navigate cultural differences and incorporate diverse musical traditions into your repertoire?

I have observed cultural differences in more or less every setting in which I work. The challenges of working through cultural differences are considerable, because we have to think about how we create musical material; what kinds of songs and other material we choose; what kind of texts we work with. But the rewards are considerable, particularly when people are engaged with creating meaning, when they author their lives and tell their stories. If they can do this through music, that’s an enormous reward for us as music educators.

How do you see music plays a role in addressing the complex social issues in today’s society like mass incarceration, peace building, migration and LGBTQ+ rights?

Music education has enormous potential to foster changes of attitudes, to generate a sense of self, to heighten awareness, to lead people towards activism. Music-making is a vital way for us to address the social issues of our time. Addressing these complex issues needs a deep understanding of history and context. It’s very difficult to understand many of the most complex social issues, such as mass incarceration, if you’re not actually engaging with people who are imprisoned, or to engage in peace-building unless you are actually in the places of tension. We don’t necessarily have to think about peace-building only in a war zone: I’ve worked with rival gangs in American prisons, and I see that kind of work as a dimension of peace-building. Music education has a vital role in addressing these issues. But it’s about how we seek to address these issues that makes the work meaningful.

How do you approach cultural sensitivity and inclusivity in your work, particularly when working with marginalized communities or communities with distinct cultural practices?

Whether one is working with Israelis, Indonesians, Palestinians, or Sri Lankans, one needs to be sensitive to different cultural settings. Every setting has its own highly distinctive context. It’s wonderful that music educators are talking about being culturally sensitive and inclusive. Having worked with people with severe mental health challenges, or transgender refugees, I have had to find distinct cultural practices that makes sense for them. I can recall an encounter in a Boston prison, where a participant said that he didn’t want to sing white music. And there’s an important lesson here – music is racially constituted.

In your experience, how does music serve as a tool for healing?

I talk about resilience and healing quite a lot, but it’s difficult to know the extent to which I am creating opportunities for healing. People often say that they feel my work provides them with opportunities for healing. Since I’ve worked with so many people who have experienced trauma, sexual violence, and other forms of brutality, it is important for me, as a music educator to think that everything I do should be about about healing and resilience. It should be more than just avoiding harm. The unfortunate reality is that very often we make mistakes in our work. We might make repertoire decisions, choose ways of speaking, or construct our practice that may have unintended negative consequences. We have to understand where we’re working and what that might mean for people who have experienced trauma. And I should say that people experience trauma in a vast number of settings.

Given the global challenges we face today, such as increasing polarization, associate injustice, what do you believe the are the most pressing ways for music educators and artists in fasting, understanding, empathy, and positive change?

Our world is increasingly polarized, and we have social injustice. This is why we have to bring people together, and that’s the first priority. We must find ways to bring people together. Thoughtful and compassion-focused music-making can bring people together, and can create a space in which we construct empathy and understanding – to allow for difficult conversations to take place. How can we shine a light on injustice through music-making? That goes beyond the repertoire that we perform, but it also takes into account where we perform, how we perform, and so forth.

Music education can be supremacist, humiliating, and epistemologically violent. So, how can we turn away from such practices? How can we actually make music practices healing so that people can walk away from every rehearsal, every class, every session and feel more whole, more healed, more engaged with themselves. And those are the critical questions for us as music educators.

How would you encourage the future music educators to be active and take a role as changemakers in the society?

For me it’s very clear. I ask them if they are happy with today’s world. When I ask this question, in fact, I’ve never heard anybody say they are happy with the state of the world. Well, as the great American writer, Howard Zinn, said, you can’t be neutral on a moving train. So if you’re not happy with the state of the world, what are you doing to make the world better? How can your work as a music educator make the world a better place? And the response to that question is different for everybody, because we work in different contexts and address different issues.

What’s the role of international gatherings like ISME World Conference in changing how we see the global issues that are facing us?

I’ve been going to ISME since the 1980s. It has been a wonderful place for me to engage with people who are doing meaningful work, to understand music educators in different parts of the world, and to have my ideas interrogated and critiqued. I think that international gatherings such as ISME are enormously vital. We are at a time of intense global problems and for us to be making music as perhaps we made 50 years ago without attention to global problems is not the way we should be going forward. And ISME conferences can help us to imagine and build a better world through music education.

André De Quadros is one of the international keynote speakers at the 36th World Conference of ISME – international society of music education, held in Helsinki next Summer.