‘In the name of the gays and the arts’ – LGBTQ+ student community organises low-threshold queer activities

Q.U.N.T., a community founded by Uniarts students, builds spaces within the university that are braver, more open, free of hierarchies, and first and foremost queer.

Nunu Anundi (they/them), student of painting, and Anna Pietilä (they/them), student of performing arts design, are seated at the Kookos building Tori lobby. On the tables in front of them are laid out two pride flags and a number of event posters all featuring the letters Q, U, N, and T.

‘We were thinking we’d like to show you our locker’, says Pietilä. When Willjam Tigersted (he/they/she), studying acting in the Swedish-language programme, joins our group on Tori, we head towards the locker.

On the door of the third-floor locker are a few stickers that set it apart from neighbouring, cream-coloured and sticker-less doors. Inside the locker, equipment is stored from past events and in waiting for future ones – pride flags, rainbow-striped stickers and Fat Lizard reflectors left over from a sponsorship of a bygone event.

The locker is a joke that works on many levels – albeit better in Finnish. In Finnish, the word for ‘locker’ – kaappi – also stands for ‘closet’.

‘It’s where we belong’, remarks Tigerstedt. LGBTQ+ minorities grow up inside the closet, come out of the closet, and occasionally find themselves back inside one. The locker/closet is also a humorous answer to a question about queer spaces within the walls of Uniarts: officially, there are none.

During the academic year 2021–2022, a group of students decided that it is time to build some. Q.U.N.T. was born: a community and platform, whose active members Anundi, Pietilä and Tigerstedt are and whose aim is to bring together minorities within Uniarts. As its methods, Q.U.N.T. uses parties, game nights and a conversational culture rooted in openness.

Queer? Unbelievable Never stop The fun

The core mode of operation for Q.U.N.T. is to arrange low-threshold, fun activity. This goal may seem rather typical for a student-driven community, but it has its reasons: ‘After all, in my experience, this is quite a hard place’, says Anundi. Studies at Uniarts can be draining and individualistic and the academies stand quite afar from each other in many respects. The ideal of Q.U.N.T. is to counterbalance all of this.

Organising fun and easy community activities is also poignantly important for minority students. Many queer communities focus on discussions on societal issues, which is important, but can also be very draining, as Pietilä puts it.

‘That was the idea behind Q.U.N.T., that there would also be easy-to-join, fun activities.’ Constructive and critical discussion surely takes place at Q.U.N.T. events as well, but it is not a prerequisite of participation, and it can be had while doing crafts at a workshop or playing a board game.

Anundi, Pietilä and Tigerstedt emphasise that Q.U.N.T. is free of internal hierarchies: all members of the community are equal and there are no leaders. ‘Anyone can suggest an activity or something to do, political acts, events, or just something they would like to do and ask for people to join in’, says Pietilä.

This practice has shown to be rewarding yet challenging in a structurally hierarchical institution like the university. From the locker/closet, we traverse the university corridors to continue our conversation in a meeting room, and the space is shock-full of signs of university and art-world hierarchies: it can only be reserved by a staff member, on the wall there is a Sinikka Tuominen painting from the National Gallery collection, and right outside the door, cake and coffee are served in honour of vice rector Marjo Kaartinen who is leaving the position.

Or maybe the impression has been warped after focusing on the themes of the interview too much. The hierarchy becomes undone – even if only slightly – when the door opens and an invitation is uttered to have some cake, while there’s still some left.

Q.U.N.T. is primarily a community for and by queer people, but what this means is everyone’s personal business. ‘From the start, it’s been our intent that we don’t define your queerness’, says Tigerstedt. ‘Whether you’re curious in some way or still questioning – you’re welcome.’

Pietilä continues: ‘We aim to hold one bigger, free entry event in a year. Something like that I could recommend to someone, who’s still thinking “is this for me” or whether they’re a part of the LGBTQ+ community. You can just come and see whether this is something that feels right for you.’

Joining Q.U.N.T. is simple. Information about activities and events are shared in the community’s Facebook group, in the WhatsApp chat for active members, and the university’s mailing lists. The threshold to join is low and no commitment is required. ‘Even the word “joining” sounds quite formal’, says Anundi, ‘rather, you can just be, listen and sniff around.’ Pietilä completes the thought: ‘Softly and according to your own resources.’

Welcome are students, university staff as well as queer artists from outside the university. In the Facebook group there are many people working in the arts from outside Uniarts and events have been organised, for instance, with the MYÖS collective that specialises in producing more diverse and safer club events.

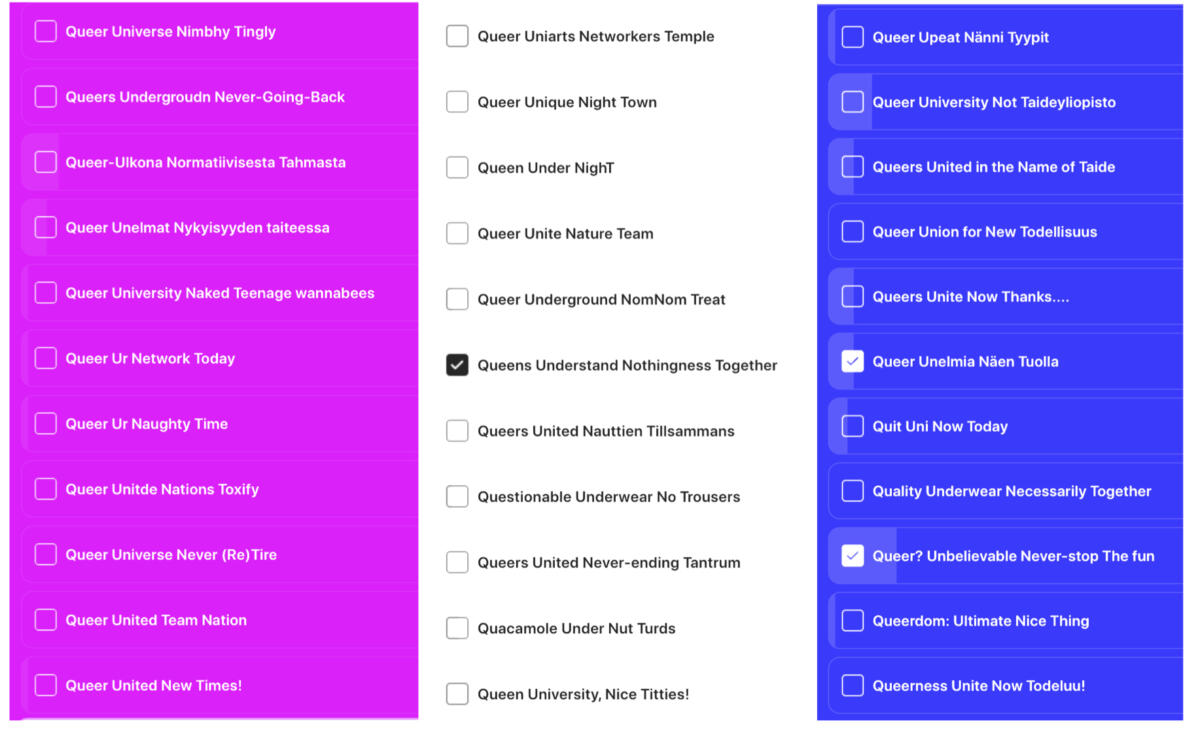

And what does the acronym Q.U.N.T. stand for? The name alludes to the ‘c-word’, the degrading meaning of which is reclaimed and turned into something fun. ‘But in addition we made a game out of all the things it could stand for’, says Pietilä. Suggestions were collected at the very first Q.U.N.T. event and good ones came in in spades. ‘Queer University, Not Taideyliopisto’, Pietilä reads off a list, ‘Queers United in the Name of Taide. Queers Understand Nothingness Together.’

The name has potential to mean anything, yet it means nothing. The meanings are reflective of the liminality distinctive to everything queer: they exist between boundaries and categories, escape singular definitions, and offer room for different methods of interpretation.

A space that is first and foremost queer

Q.U.N.T. began as an initiative by Theatre Academy first-year students in the spring of 2022, but the exact moment of inception is hard to pinpoint.

‘Similar ideas were thrown about in various instances’, says Tigerstedt. ‘One hand pondered on it, and another said it out loud. A third had also pondered that is would be nice if there were some kind of queer community.’ A first unofficial gathering was held that eventually led to an event invitation on the Uniarts students’ mailing list with the introductory words: ‘It is time for us to meet up in the name of the gays and the arts.’

The same invitation asked: ‘Because all spaces are predominantly straight, could this community build a space that is first and foremost queer?’

‘It’s a relevant question, still’, says Pietilä. At the heart of the community has been from the start – and still is – a need for communal, queer spaces.

Has the community managed to build such spaces? ‘Yeah, for sure’, Pietilä exclaims and Anundi joins in: ‘ Yeah yeah, yes.’ Well, what kind of queer spaces does Q.U.N.T. occupy now, more than two years after its founding?

‘The closet’, (the locker, remember), says Tigerstedt. Laughter. In addition to the locker, the community makes its home in the virtual spaces of the Facebook and WhatsApp groups. Spaces are occupied and created also in Q.U.N.T. events, the biggest of which have been held at Vapaan Taiteen Tila. ‘It would be so important that VTT would be able to operate in one form or another after 2024’, says Tigerstedt.

Uniarts has continued to fund Vapaan Taiteen Tila until the end of this year. The university student union stated in their newsletter on 28 May that they are looking for new funding partners and continuing discussions with the university to secure funding until the end of 2026. Tigerstedt speaks for the diversity of the venue, which makes it a natural choice for an event space for Q.U.N.T. as well.

‘VTT is also open for everyone’, continues Pietilä and so compares the venue to the university’s own facilities. ‘As a rule, it has been really difficult to meet within the university. That involves a ton of negotiation.’

In the autumn of 2022, a meet-up was organised on the Sörnäinen campus at evening hours and the atmosphere was marked by a worry over the proper use of the facilities. The importance of this had been emphasised by the staff and there was a drive to do everything right, so the facilities could be used again in the future. When the building’s alarms went off, cold shivers started down the spine: we’ve messed something up, left a wrong door open or something. Soon, it turned out that the alarms had been set off by the November 2022 water damage in Mylly.

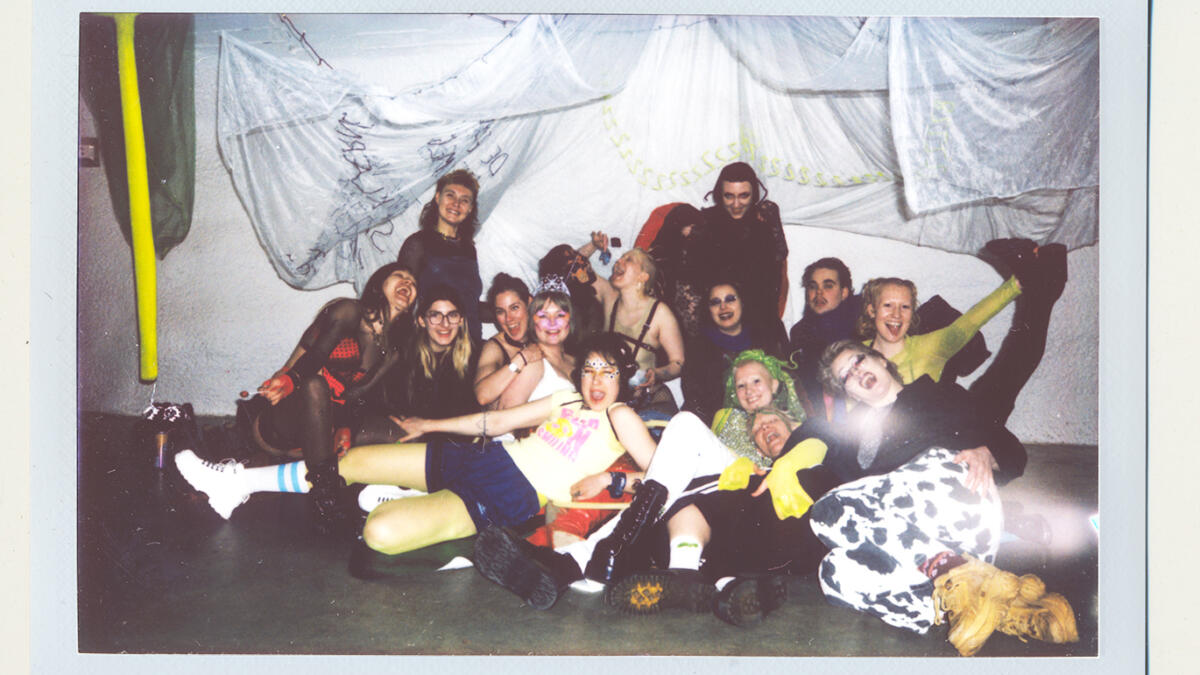

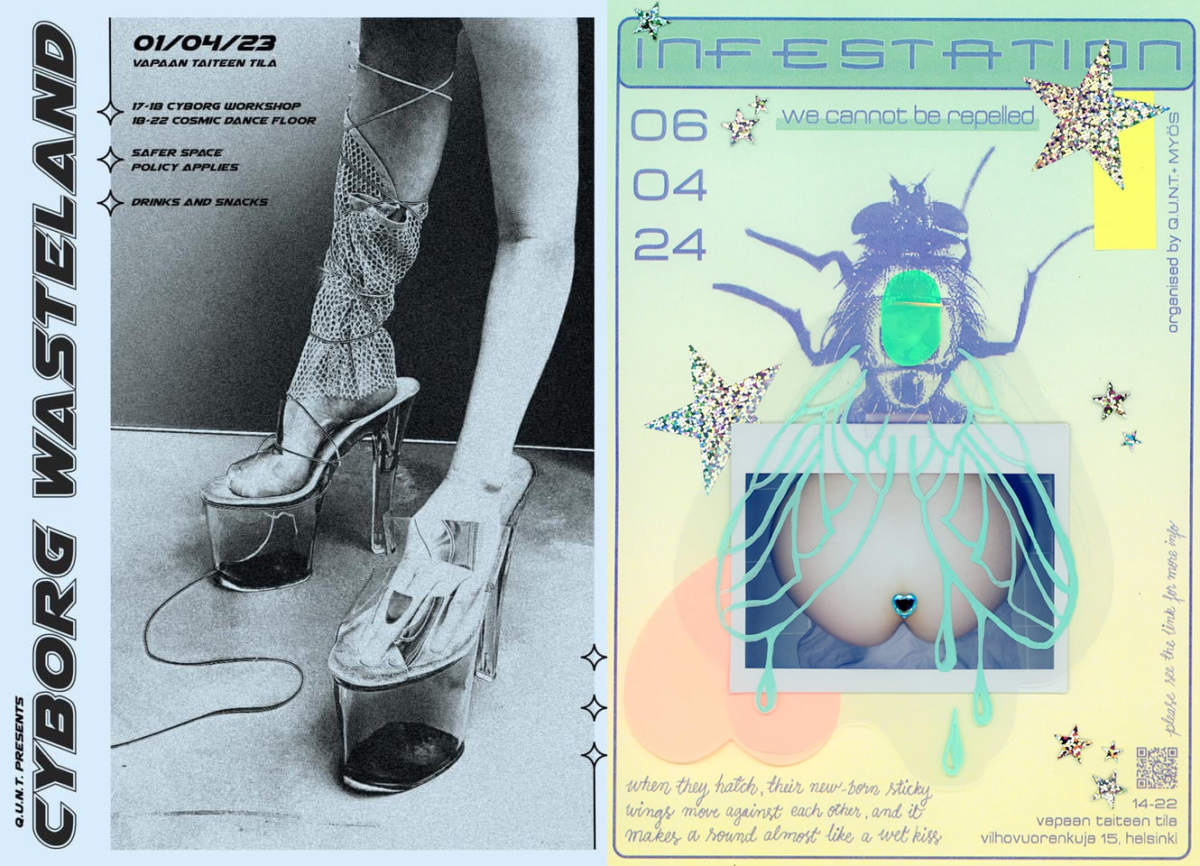

When thinking about the most memorable moments of past events, the water damage incident comes up, whether you want it to or not. ‘It was such an absurd situation’, recalls Anundi. More positive highlights, luckily, are more numerous: ‘The first big event was somehow special and wholesome’, says Pietilä. ‘People showed up with such curiosity.’ From the other bigger events, organised with MYÖS, memorable details include the DIY-spirit of 2023’s Cyborg Wasteland and how big of a production 2024’s Infestation developed into.

Smaller-scale highlights paint a picture of the variety of Q.U.N.T.’s events and activities: there’s been bingo, games, a celebrated costume workshop, an idea wall used to inspire future events, and a pay-what-you-can café, the profits of which were sent to humanitarian aid in Palestine. ‘Functionality is an important factor in our events’, says Anundi, ‘it can be easier to spend time in a space where there are activities and things to do.’

Towards braver spaces

This philosophy of building spaces according to the needs of those using them, is very present in all of Q.U.N.T.’s operations. In the events, all participants are expected to subscribe to the so-called safer space principles – zero-tolerance on discrimination, everyone’s right to their bodily autonomy and the self-definition of their identity – but the concept itself is not adopted without critique.

‘Safer space, as a term, it’s often thought to refer to some existing space, but rather it’s an ongoing process of growth and dialogue’, says Pietilä. The experience of safety or lack thereof is influenced by each individual’s experiences and background, and no space can be guaranteed to be completely safe for all occupants. ‘We create spaces as a community and those spaces are re-defined each time.’

Anundi refers to an idea of safe moments that caught their attention at the Queer Labour course at the Nida Art Colony in Latvia. The idea, shared by the course’s facilitator Vidisha-Fadescha and attributed to their friend Kinkinella, sees safety as being created in moments: moments, in which all participants feel a sense of safety, but also in moments, where boundaries are broken and feelings are hurt. And possibly most importantly of all, in moments that follow these transgressions.

‘We always end up offending each other, whether we want to or not. What’s important is what happens after. We need to focus on communication so we can create safe moments together and learn together. Failure is a part of the deal.’

In Anundi’s experience, open-minded conversations happen naturally within Q.U.N.T.: ‘A kind of soft, gentle and sensitive communication appears to be something that’s valued in this community. Finding harmony between different people of different backgrounds.’

To replace ‘safer space’, alternative terms that better recognise the sensitive and mutating nature of the spaces in question have been suggested. From these, mindful space or braver space, for instance, resonate well with the members of the community.

The active members of Q.U.N.T. wish that the university, too, would focus on building besides safer, also braver spaces. For example, by creating diverse and open forums of discussion. Here, the members recall a discussion from the past academic year regarding the use of mailing lists. When the students’ mailing list was used to distribute political appeals related to the crisis on the Gaza strip, rector Kaarlo Hildén pleaded for students’ right for a safe environment and reminded that the mailing list was meant for study-related matters.

Thus measures taken to increase safety can very well create experiences of the opposite for some groups, and the members of Q.U.N.T. question the claim that universities are apolitical institutions, which came up in the aforementioned discussion: “There’s no such thing as an apolitical institution’, says Pietilä.

In meeting room 4, while sampling the farewell cake of the vice rector, the discussion turns towards the future of Q.U.N.T. and the active members’ own farewells, somewhere in the horizon:

‘It would be amazing, if Q.U.N.T. continued on after we graduate’, says Tigerstedt. However, a worry persist that the community is still quite unknown. Q.U.N.T. is not in the closet, but ‘it kind of is, a little’: sometimes you forget to tell people about the community and the lack of internal hierarchies make it seem vague and amorphous for outsiders. ‘Some have come to me and asked, if I’m Q.U.N.T.’, says Pietilä.

While Pietilä is certainly not the leader of Q.U.N.T., the asker is not entirely off-track: Q.U.N.T. is its members. The queer spaces built by the community are not confined within the metal walls of the locker, but are constructed out of safe moments, communication and people. Future generations of students can continue re-shaping the community and the spaces it occupies.