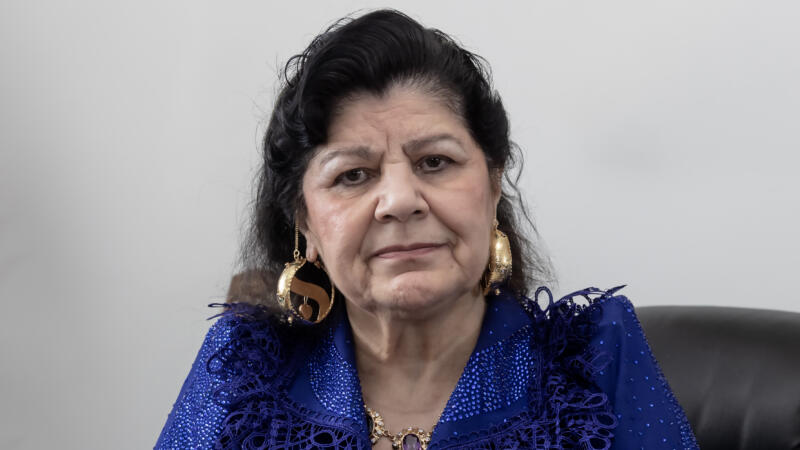

Honorary doctor Susanna Mälkki: A messenger for contemporary classical music

Susanna Mälkki has done commendable work in raising the public profile of contemporary classical music, and she considers herself an enabler whose mission is to support composers.

“I remember that moment well – suddenly everything felt so right somehow,” says conductor Susanna Mälkki, who will be conferred the title of honorary doctor at Uniarts Helsinki in August.

“I was the conductor standing in front of a small practice orchestra for the first time. It was like an epiphany, and I understood that this is exactly what I want to do.”

Mälkki was a gifted cellist at the time, and she studied at Edsbergs musikinstitut near Stockholm. Originally, she did not even want to participate in the conductor class led by Esa-Pekka Salonen that was organised alongside her regular studies.

“Salonen worked as the chief conductor of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. I found it absurd and embarrassing that hacks like us would wave the baton under the tutelage of a master like him,” Mälkki says.

After the classes, life seemed to continue the way it used to. Mälkki spent a year studying cello at the Royal Academy in London, and after that, she finished her studies at the Sibelius Academy.

All this time, however, she quietly eased into the idea of pursuing conductor studies. After completing a cello diploma, Mälkki applied to a conducting programme without telling anyone about it.

“I didn’t want to have to hear any tiresome comments about it,” she says.

Mälkki was admitted as a student, but the same spring, she had also auditioned for the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra and got picked.

“I decided to accept both offers,” Mälkki says.

Cello and baton

During the first two years of her conductor studies, Mälkki served as the solo cellist of the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra and flew frequently between Finland and Sweden, alternating between the two lives. Orchestra work added an extra layer to the studies.

“I got to not only follow the work of a conductor close up but also make my own mistakes on the podium. My interest in the profession grew exponentially,” she reminisces.

Mälkki has never had one specific role model as a conductor, but she admits that she has admired the work of several Finnish and international conductors. As an example, Mälkki mentions that Estonian Neeme Järvi, the former conductor of theGothenburg Symphony Orchestra, was “extremely talented in technical aspects” and an influence on her own understanding of the importance of a conductor’s technique.

“It was so easy playing with him. I didn’t have to think much at all – watching his hands was enough,” Mälkki says.

She says that during her studies in Stockholm, she often went to concerts and really came to realise the tremendous difference that a conductor can make in how an orchestra plays.

“In my own orchestra practices, different conductors came to train us. I played the cello, but I observed all of what was going on also through the eyes of a conducting student and reflected on what works well and what doesn’t.”

Major turning points

Many people find that Mälkki made her breakthrough when she was the conductor for the operaPowder Her Face composed by Thomas Adès. Mälkki agrees.

“But I maybe didn’t understand it back then,” Mälkki says.

“Actually, thinking about it today, I kind of don’t understand how I was able to conduct it – Powder Her Face is a really difficult piece!”

When looking back on her career path, Mälkki can determine several turning points where she gained momentum from her cooperation with composers. After Powder Her Face, Adès

invited Mälkki to London, and a few years later, composer Pierre Boulezpresented her the invitation to come to Paris and work as the artistic director of Ensemble intercontemporain, which is an ensemble dedicated to contemporary classical music.

Mälkki’s collaboration with Italian composer Luca Francesconi, on the other hand, led her to La Scala, the famous opera house in Milan, where she made the debut as the first woman conductor of the opera house’s history.

“I got the chills in that magical moment of looking down at the orchestra pit at La Scala and understanding how that was the place where the entire history of opera has taken place.”

Mälkki started as the chief conductor for the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra in 2016, making her the first woman in the post. The seven-year stint meant a lot to Mälkki.

“Especially on a sentimental level. It was the orchestra of my hometown and the first orchestra I had ever heard play.”

Wonders and challenges of contemporary classical music

Mälkki says she is aware that for many audience members and even musicians, contemporary classical music is almost like the necessary evil. But personally, she finds it an exquisite window to the world.

“It is rare that contemporary classical music evokes the same kinds of emotions than an opera by Wagner, but that’s not what it tries to do, either. After all, it’s not like we want to only reproduce and hear variants of the same thing that has already been done.”

Getting acquainted with and training an orchestra to play a contemporary classical music piece often takes considerably more work than a piece by Bach or Sibelius that everybody knows.

“But in a sense, I’m fearless, and I’m not afraid of taking up a task like this. The importance of the work weighs more,” Mälkki points out.

Classical music is often a very conservative form of art that is expected to represent beauty and harmony. Compared to the standard classical repertoire, contemporary classical music can, in fact, sound downright grating, as Mälkki puts it.

Often, new works contain powerful substance, however, which can only be fully learned and understood by listening. Mälkki encourages people to boldly seek out new horizons.

“As a comparison, there’s really nothing more to it than occasionally going to the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma instead of the Ateneum Art Museum.”

A partner and an enabler

When discussing Mälkki’s career, one must not forget her collaborations with Kaija Saariaho. Her first introduction to Saariaho’s music happened at the Turku Cello Competition in 1994, when Saariaho’s avant-garde composition titled Petals was included as the competition’s mandatory piece.

“Back then, it was completely new and foreign music to me,” Mälkki says.

Mälkki succeeded in her rendition, however, as she won the competition. She presumes that Saariaho became aware of her already back then, even though they did not meet at the competition.

Later by Saariaho’s request, she conducted her orchestral pieces at the Helsinki Festival, assisted Esa-Pekka Salonen on Saariaho’s opera called L’Amour de loin and conducted the premiere of La Passion de Simone in Vienna. Mälkki also visited New York’s Metropolitan Opera with Saariaho.

“Maybe what she saw in me was a person who understood her music and who really wanted to put her mind to it. We had a natural dialogue going on between us,” Mälkki says.

In 2021, Mälkki conducted the premiere of Saariaho’s last opera, Innocence, in Aix-en-Provence. She says that the conductor of a premiere is a crucial partner for a composer.

“Over the years, I’ve started to have an even stronger sense of my mission in the field of contemporary classical music: I’m kind of like an enabler and a messenger for composers. The premise of our cooperation is mutual trust, and we find the core of the work and create something completely new together.”

Art is about making a connection

The way Mälkki sees it, art is the most profound essence of culture and part of humanity that helps us process life and channel various emotions, both happy and sad ones. In a way, nothing is more important than that.

Mälkki would hope to see artists, art and creative thinking being utilised more extensively in society, not just through the lens of performing arts and entertainment.

“Art and expression in its various forms open up an abundance of interaction and other possibilities. That’s why the field of arts should, in fact, be wide-ranging, and that’s why children, especially, should be given the chance to discover the magical world of art,” Mälkki says.

Due to the uncertainties of the field, many people in the arts feel the pressure to gain success.

“But how do you define success? At the end of the day, art is a connection that you create with the audience and nothing that can be measured by numbers,” Mälkki says.

“I, of course, hope that as many people as possible would find their way to the arts one way or the other. But art can be remarkably good and impressive and I may find that the artist has done a good job even when the art never reaches a big audience.”

Many artists and institutions need financial support, like grants and project funding, for creating works, but the current government has planned major cuts on the cultural sector. Mälkki finds the situation unfortunate and very short-sighted.

“Culture may be a thing to boast about, but the same people may want to saw off the branch that culture is sitting on.”

Explorer of music

First years in the field are often tough for conductors. Major new works, constant travelling and changing from one work community to another may feel straining, making life seem disconnected.

“Now that I also have an established career, I can make choices and organise my life in a way that I don’t need to travel the world all the time,” Mälkki says.

Then again, she thinks that this musical exploration and staying on the move fits her.

“My job is definitely my passion, and I still have new dreams that I want to pursue professionally.”

What might those be?

“Theatre is interesting to me, and I want to do more operas. There are many interesting pieces in the opera repertoire. My particular wish is to conduct Wagner.”

Text: Elli Collan

Uniarts Helsinki conferment event, the ceremonial conclusion of university studies, will be held in Helsinki from 16 to 18 August 2024. The ceremony will feature the conferment of degrees on master’s graduates and doctors from the university’s academies. Additionally, honorary doctorates will be conferred on eight individuals who represent Finnish or international pioneers and influential figures in their fields and who have advocated for arts education or advanced the societal role and significance of the arts.

The honorary doctors have been selected by the boards of the Academy of Fine Arts, Sibelius Academy and Theatre Academy and the board of the University of the Arts Helsinki. Being conferred an honorary doctorate is the highest recognition bestowed by the university.